Horsepower: Trotting After George Stubbs

By Richard Carreño

I've been a groupie of George Stubbs, the 18th-century English sporting artist, for as long as I can remember. Well, ever since, as a teenager, when my father trotted me by the Tate Gallery (as it was known then) to see its Stubbs collection. Over the years, I've followed up with pilgrimages to major collections at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; the Woolavington Collection, Northampton; and, in the 1980s, I even made my way to Worcester, Massachusetts, to the Public Library there, to view one of the rare full sets of Stubbs' anatomical drawings of the horse.

Fortunately, for American fans of British sporting art, some of the world's greatest collections of this genre -- and thanks largely to the late horseman and art collector Paul Mellon -- are found in the United States, at the Richmond Museum of Fine Arts and, most significantly, at Yale, at the Center for British Art. At New Haven, scores of great works by Stubbs and other period artists (Alfred Munnings is just one) are showcased cheek-by-jowl, floor by floor. (Remember those anatomical drawings from Worcester? They're now at the Center for British Art, as well).

Closer to home, at the Museum of Art, Philadelphians can get a local taste of Stubbs' oeuvre. Three pictures, The Grosvenor Hunt, Hound Coursing a Stag, and Labourers Loading a Brick Cart-- albeit not of such great stature and fame as Whistlejacket (at the National Gallery, London) or Horse and Lion (at Yale) are on permanent display, this time thanks to a gift by John H. McFadden, one of the museum's founding donors.

What is less known -- and rarely seen -- is another Stubbs work (one of those famous anatomical plates I first saw in Worcester) that's been squirreled away at the University of Pennsylvania over the years without much notice, nor fanfare. That is, until now.

Sometimes being reminded of Stubbs requires a block-buster, such as was the case with the 'Stubbs and the Horse' retrospective that toured the United States in 2005. (I saw the collection at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore).

Other times, there's a peg to a new unveiling. The bicentennial of his death is the latest advertised reason for a newest show of Stubbs' virtuoso repertoire of paintings of wildlife, dogs, barnyard animals, and most important, of course, horses, which opened in early February at the Frick Collection in New York. The show was originally organized by the Walker Art Galley in Liverpool, and was at the Tate Britain (what the Tate Gallery is now called) before it moved to New York.

'No other 18th-century British painter who was so successful in his own lifetime was so quickly forgotten after his death,' noted Denise Allen, associate curator of the Frick Collection in a current museum publication, which I picked up when I visited the exhibit.

Interestingly enough, as I mentioned, a bit of the painter is now also getting a simultaneous showcase in Philadelphia. To be sure, the Stubbs piece now on display at a local exhibit, at the Kamin Gallery, at Penn's Van-Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, is only a tiny Stubbs starter-kit, just one of the 37 legendary anatomical plates by the artist. Moreover, this one item was seemingly an after-thought.

When I called Lynne Farrington, of the Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library, a week or two before the Van Pelt exhibit debuted in mid-March, she told me that the Stubbs plate would not be on display. Yes, she said, the drawing is part of the larger collection of horse-related art collected by the 19th-century Penn professor Fairman Rogers, which comprises the corpus of the current exhibit, 'Equus Unbound: Fairman Rogers and the Age of the Horse.' Unfortunately, she went on, because of the plate's 18th-century provenance, the work falls outside the 19th-century scope of the show.

I was pleasantly surprised, however. When I turned up at the opening, the Stubbs drawing of 'the bones, cartilages, muscles, fascias, ligaments, nerves, arteries, veins, glands....' published in 1766 -- by now an 'old friend,' after my first viewing more than 20 years ago in Worcester -- was there. In fact, up front, in a place of honor.

In addition, I wasn't disappointed with the show as a whole. Curator Ann Greene, a Penn lecturer and author of Harnessing Power: Industrializing the Horse in Nineteenth-Century America, to be published by Harvard next year, picked well from the abundant Rogers Collection of Books on the Horse and Equitation.

Rogers, himself, a Penn trustee, co-founder of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, and coaching expert, was, if anything, eclectic. Works in the collection from 18th century 'reflect the traditional view of horses as noble creatures' and 'the interests and perceptions of those who had the means to own and utilize horses, namely the upper classes.' But Rogers, though a bluestocking Philadelphian himself, had more expansive ambitions, as well, collecting works from equine medicine to horseshoeing.

No less a figure than Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) is also represented. Sixteen prints of 'an electro-photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements, 1872-1885,' published by Penn in 1887, are familiar from re-publication -- but welcome, at least, for me, to see in an original printing.

Go to see the Stubbs. Stay to see the rest.

'Equus Unbound: Fairman Rogers and the Age of the Horse,' in the Kamin Gallery, Van-Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania, is free and open to the public. The exhibit closes June 15. Photo ID is required.

(This article is also available at BroadStreetReview.com in a slightly different version).

By Richard Carreño

I've been a groupie of George Stubbs, the 18th-century English sporting artist, for as long as I can remember. Well, ever since, as a teenager, when my father trotted me by the Tate Gallery (as it was known then) to see its Stubbs collection. Over the years, I've followed up with pilgrimages to major collections at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; the Woolavington Collection, Northampton; and, in the 1980s, I even made my way to Worcester, Massachusetts, to the Public Library there, to view one of the rare full sets of Stubbs' anatomical drawings of the horse.

Fortunately, for American fans of British sporting art, some of the world's greatest collections of this genre -- and thanks largely to the late horseman and art collector Paul Mellon -- are found in the United States, at the Richmond Museum of Fine Arts and, most significantly, at Yale, at the Center for British Art. At New Haven, scores of great works by Stubbs and other period artists (Alfred Munnings is just one) are showcased cheek-by-jowl, floor by floor. (Remember those anatomical drawings from Worcester? They're now at the Center for British Art, as well).

Closer to home, at the Museum of Art, Philadelphians can get a local taste of Stubbs' oeuvre. Three pictures, The Grosvenor Hunt, Hound Coursing a Stag, and Labourers Loading a Brick Cart-- albeit not of such great stature and fame as Whistlejacket (at the National Gallery, London) or Horse and Lion (at Yale) are on permanent display, this time thanks to a gift by John H. McFadden, one of the museum's founding donors.

What is less known -- and rarely seen -- is another Stubbs work (one of those famous anatomical plates I first saw in Worcester) that's been squirreled away at the University of Pennsylvania over the years without much notice, nor fanfare. That is, until now.

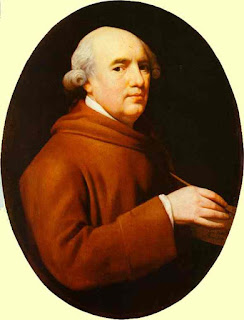

It isn't surprising that Stubbs (1724-1806), given his almost inbred renown among sporting art connoisseurs trolling Bond Street galleries and Mayfair auction houses and, similarly, among effete interior decorators of geezer men's clubs and cholesterol-laden steak houses, needs be reintroduced to the wider art world from time to time.

But Stubbs is hardly just an artist for the horsey set or its wannabes. Since the ancient Greeks, horses have been portrayed with reverence, romance, and with varying degrees of accuracy. That changed forever with Stubbs, the son of a tanner who eventually transformed the way artists depicted horses and sporting scenes. What 19th-century English photographer Eadweard Muybridge did in photography (capturing, in never-before accuracy, the gaits of horses in series of stop-motion pictures), Stubbs, a hundred years before, was also able to do in oil, harnessing a new realism (based on his dissections of the horse, depicted in his pen-and-ink plates) to the canvasses of sporting art.

Sometimes being reminded of Stubbs requires a block-buster, such as was the case with the 'Stubbs and the Horse' retrospective that toured the United States in 2005. (I saw the collection at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore).

Other times, there's a peg to a new unveiling. The bicentennial of his death is the latest advertised reason for a newest show of Stubbs' virtuoso repertoire of paintings of wildlife, dogs, barnyard animals, and most important, of course, horses, which opened in early February at the Frick Collection in New York. The show was originally organized by the Walker Art Galley in Liverpool, and was at the Tate Britain (what the Tate Gallery is now called) before it moved to New York.

'No other 18th-century British painter who was so successful in his own lifetime was so quickly forgotten after his death,' noted Denise Allen, associate curator of the Frick Collection in a current museum publication, which I picked up when I visited the exhibit.

Interestingly enough, as I mentioned, a bit of the painter is now also getting a simultaneous showcase in Philadelphia. To be sure, the Stubbs piece now on display at a local exhibit, at the Kamin Gallery, at Penn's Van-Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, is only a tiny Stubbs starter-kit, just one of the 37 legendary anatomical plates by the artist. Moreover, this one item was seemingly an after-thought.

When I called Lynne Farrington, of the Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library, a week or two before the Van Pelt exhibit debuted in mid-March, she told me that the Stubbs plate would not be on display. Yes, she said, the drawing is part of the larger collection of horse-related art collected by the 19th-century Penn professor Fairman Rogers, which comprises the corpus of the current exhibit, 'Equus Unbound: Fairman Rogers and the Age of the Horse.' Unfortunately, she went on, because of the plate's 18th-century provenance, the work falls outside the 19th-century scope of the show.

I was pleasantly surprised, however. When I turned up at the opening, the Stubbs drawing of 'the bones, cartilages, muscles, fascias, ligaments, nerves, arteries, veins, glands....' published in 1766 -- by now an 'old friend,' after my first viewing more than 20 years ago in Worcester -- was there. In fact, up front, in a place of honor.

In addition, I wasn't disappointed with the show as a whole. Curator Ann Greene, a Penn lecturer and author of Harnessing Power: Industrializing the Horse in Nineteenth-Century America, to be published by Harvard next year, picked well from the abundant Rogers Collection of Books on the Horse and Equitation.

Rogers, himself, a Penn trustee, co-founder of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, and coaching expert, was, if anything, eclectic. Works in the collection from 18th century 'reflect the traditional view of horses as noble creatures' and 'the interests and perceptions of those who had the means to own and utilize horses, namely the upper classes.' But Rogers, though a bluestocking Philadelphian himself, had more expansive ambitions, as well, collecting works from equine medicine to horseshoeing.

No less a figure than Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) is also represented. Sixteen prints of 'an electro-photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements, 1872-1885,' published by Penn in 1887, are familiar from re-publication -- but welcome, at least, for me, to see in an original printing.

Go to see the Stubbs. Stay to see the rest.

'Equus Unbound: Fairman Rogers and the Age of the Horse,' in the Kamin Gallery, Van-Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania, is free and open to the public. The exhibit closes June 15. Photo ID is required.

(This article is also available at BroadStreetReview.com in a slightly different version).