The McFadden Collection vs the Art Museum

By Richard Carreño

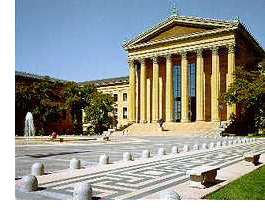

It's easy to believe, as I suspect most Philadelphians have done over the years, including myself, that the behemoth -- and majestic -- Art Museum on the Parkway has pretty much been there forever. But, in reality, unlike the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (unarguably the Art Museum's sister institution in terms of size, stature, and international prominence), the museum as we know it today was a late bloomer. In contrast to the Met, which has been on Fifth Avenue since 1880, the Art Museum will only have its 78th anniversary at its present site next month. Even then, when the building opened on March 26, 1928 the structure was hardly fully completed.

Indeed, if it weren't for a little-known, 19th-century cotton king from Philadelphia, John H. McFadden, the nascent Art Museum would have had, as well, a lot less to show. Much of its original core collection in British art (the other principal works were American) was attributable to McFadden's assiduous skill and generosity as a collector -- not to mention, of course, his vast wealth.

Despite his beneficence, McFadden built an 'or-else' clause in his bequest to the Art Museum. When he died in 1921 at 77 or 78 (different birth dates are cited), McFadden's will challenged the city to build a fitting structure within seven years, or else -- or else, he ordained, the entire collection would go to the Met in New York.

Among the oligarchical trinity of Philadelphia's first great art patrons, consisting of George W. Elkins, George D. Widener, and McFadden, McFadden is perceived as the lesser light. Maybe that's just due to a quirk of history. In every other way, McFadden was an equal in the trio -- as philanthropist, tycoon, and as voracious art collector. McFadden also looked the part in a photograph I've seen of him, rotund, fleshy, mustachioed, with a stickpin in his necktie and a favorite rose boutonniere in coat collar. Robber baron, anyone? (A slimmer, 'laundered' version of McFadden is found in 1916 oil by Philip A. De Laszlo, also part of the collection).

In several important ways, McFadden was wholly different than his philanthropic confreres, being in fact among the first Americans (during an intense period in the late 1880s when British art was at the height of its new-found popularity in America, as well as in England) to concentrate in the British oeuvre. Moreover, he took on the big-guns. Even before William L. Elkins and, clearly, before later-day Paul Mellon, Philadelphia's McFadden was competing with such rival titan collectors as Henry E. Huntington, J. Pierpont Morgan, and first Earl of Iveagh (read Guinness stout).

The result of McFadden's fixation -- piqued one supposes by a strong dose of anglophilia, as well as asthetic values, of course -- is the heart of the Art Museum's

British holdings. In all, the multi-million-dollar collection (amplified in later years by McFadden's heirs) embraces more than 40 works, including those by Constable, Lawrence, Raeburn, and among the first, if not the first, pictures by the great horse portraitist George Stubbs to find their way into Philadelphia's art patrimony.

In fact, McFadden's collection was said to be comparable to Iveagh's, now housed in Kenwood, London. At least, that's the view of Richard Dorment, a former Museum curator and the editor of British Painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1986).

'The differences between the two collections,' according to Dorment, 'may simply reflect the difference in the art markets of the later 1890s to 1916.'

McFadden himself, despite appearances, was also different than his gilt-edged contemporaries in other ways, as well. He was truly philanthropic. While living large in London for several years, he also expanded his interests in science and medicine. According to an early 20th century biographical reference work of prominent Pennsylvanians, Warwick's Keystone Commonwealth, he founded the eponymous John Howard McFadden Research Fund at the Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine to finance research into cures for cancer and measles. Other eleemosynary pursuits included Jefferson Hospital, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and, again in Britain, financing the 1914 trans-antarctic expedition of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

McFadden's colorful, dashing notions of doing good were eclectic and personal, more in line with 20th century philanthropists like the Mellons, pere (National Gallery of Art) and fils (Yale Center for British Art and the Virgina Museum of Fine Arts) and Dr. Albert Barnes (Barnes Foundation) than today's early 21st century benefactors who like to spread cash (Lenfest and Kimmel) more than vision. Like the Mellons (and the Rockefellers, too, for that matter), McFadden also believed in owning the real thing. One would be hard pressed to fathom what McFadden would make of a big-league donor of today like Bill Gates, whose idea of art is virtual art. (Gates' has his personal 'art' collection -- no kidding -- displayed on computer screens).

In contrast to the Mellons and Rockefellers, however, McFadden was his own master when it came to choosing and buying pictures. He had no 'Duveen' running interference. Rather, he purchased directly from Thomas Agnew & Co. in London (these sporting art dealers are still there in Bond Street), and never bought anything he hadn't seen.

To my mind, what's most remarkable about McFadden -- especially, given his socially-stratified era and his own immense societal privilege -- was that he believed his art belonged to the people. Even before his works wound up in the Art Museum, they were already on public display -- in a salon that became a veritable annex to the still un-built museum.

McFadden, by the bye, was also a builder. After returning to Philadelphia from London, he bought a townhouse on Rittenhouse Square (at Walnut and 19th), and proceeded to construct, in 1916, what is today The Wellington, a 15-floor high-rise and one of the first on the Square. On the top floors, McFadden installed his collection, faithfully reproducing the rooms in the mansion where his collection was formerly hung. Every Wednesday, the McFadden Collection was open to the public. His daughter Alice served tea to all comers.

It's hard to imagine any Mellon or Rockefeller -- even such a putative prolo as Dr. Barnes -- opening their dwellings to scruffy, art-hungry rabble.

Most important, of course, McFadden established the Art Museum as one of a handful of American institutions with premier permanent collections of British art. Never mind that galleries like the Yale Center and the Huntington, and the like, were never blessed with collections where tea was served to visitors.

(Richard Carreño, editor of Junto at Junto.blogspot.com, can be contacted via RittenhouseUK@yahoo.co.uk).

(A hardcopy vrsion of this article appeared in the Weekly Press of 22 February 2006 or may be seen at philly1.com).